The Ultimate Gemini AI Prompt Collection

Discover and copy the best prompts for Google's Gemini AI. Our curated collection of 1000+ tested prompts will enhance your productivity, creativity, and AI interactions instantly.

Explore Categories

View AllFeatured Prompts

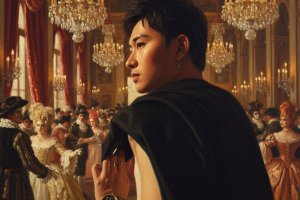

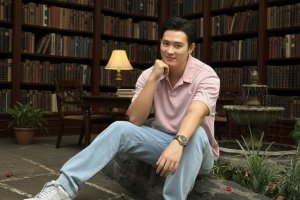

The Lord of the Rings (Orc/Monster)

Transform the person in this image into a realistic, heavily armored Orc from The Lord of the Rings. The subject should have war paint, tusks, and a d...

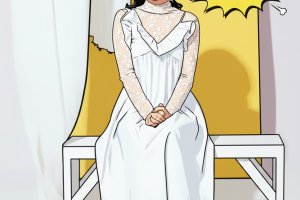

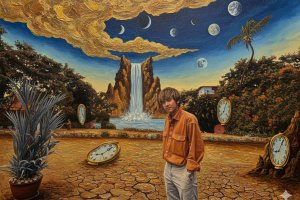

Alice in Wonderland (Tim Burton)

Transform the person in this image into a whimsical character like the Mad Hatter or Alice from the Tim Burton version of Alice in Wonderland. The out...

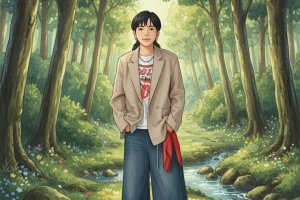

2D Animation & Anime

Transform the person in this image into a 2D anime character in the gentle, hand-drawn style of Studio Ghibli (Hayao Miyazaki). Use soft, natural colo...

Recent Prompts

Why Choose Our Gemini Prompt Collection?

Transform your AI experience with our comprehensive library of professionally crafted Gemini AI prompts designed for maximum effectiveness.

1000+ Tested Prompts

Our extensive collection features over 1000 professionally tested Gemini AI prompts that deliver consistent, high-quality results across all use cases.

Instant Copy & Use

One-click copying makes it effortless to use any prompt. Simply copy, paste into Gemini AI, and get amazing results instantly.

Organized Collection

Browse our well-organized prompt categories including writing, coding, creative tasks, business, and more to find exactly what you need.